Two small holes allow a glimpse of what lies behind the weathered wooden door. In a separately published manual, Duchamp provides instructions on how to install this particular work. His concept goes back to what is collectively known as “peep media” and is widely associated with changes of perception and experimentation either enhanced by optical devices such as lenses, telescopes, microscopes or by simply looking through a little hole into an expanding space that usually lies hidden behind.

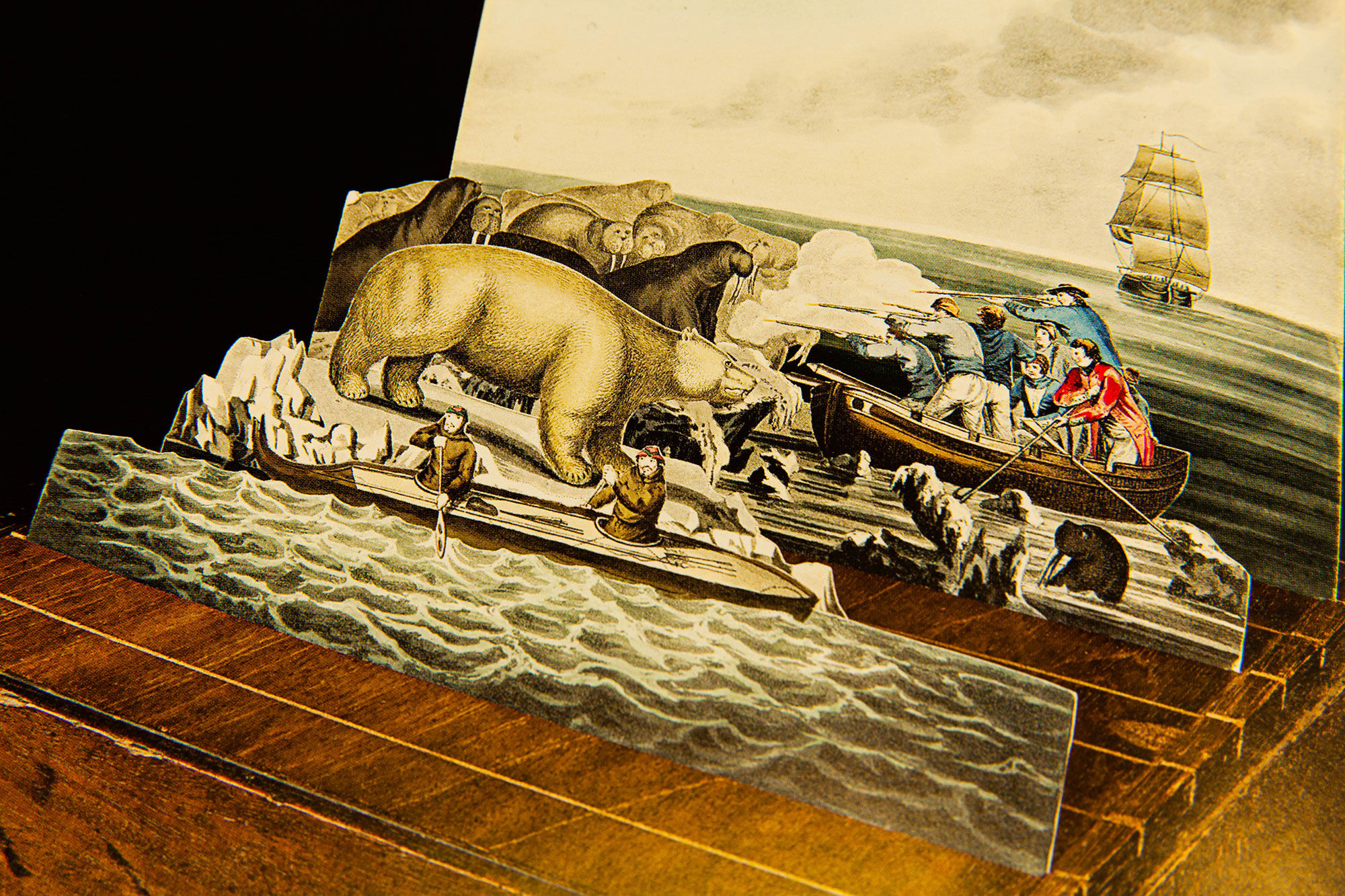

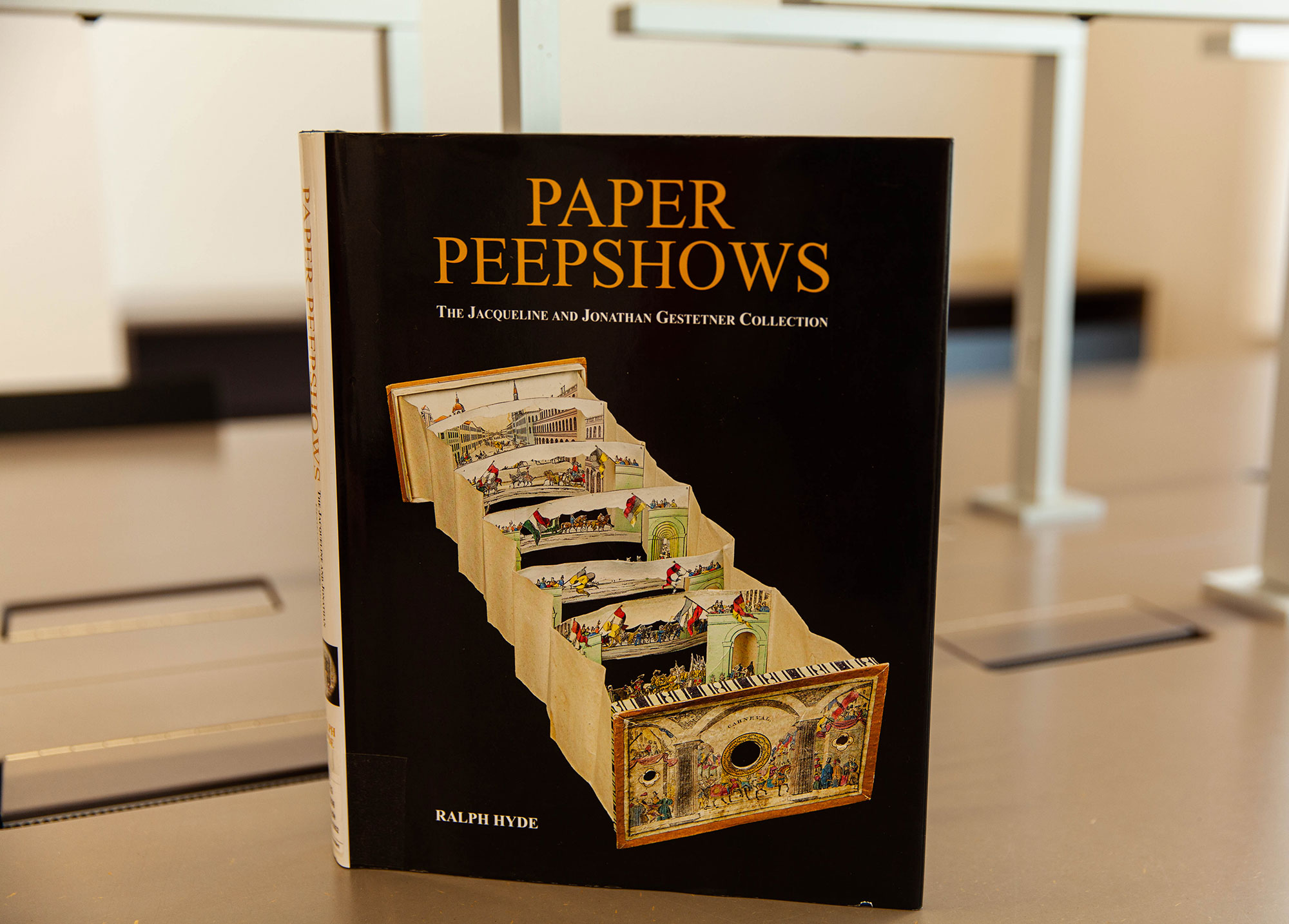

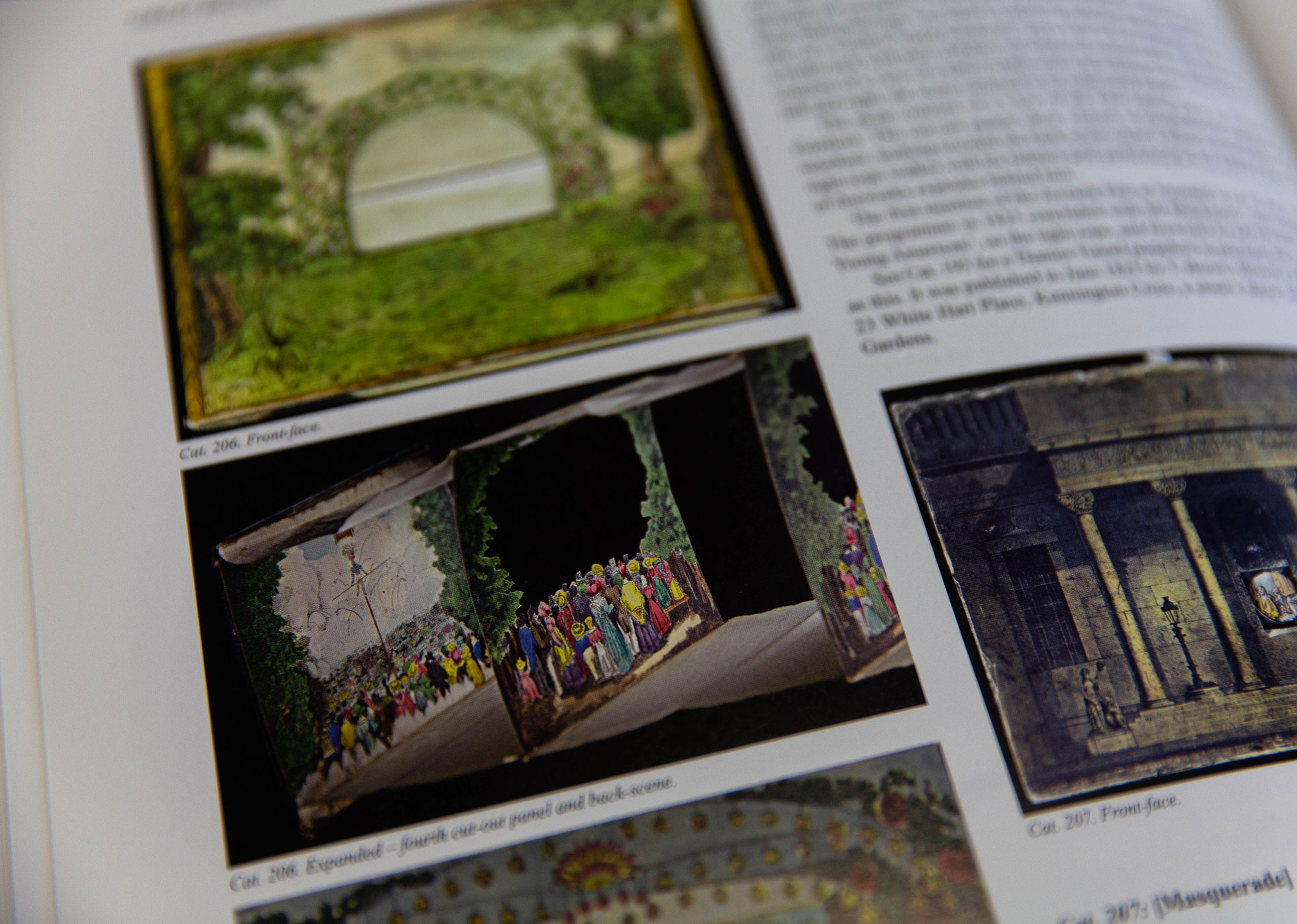

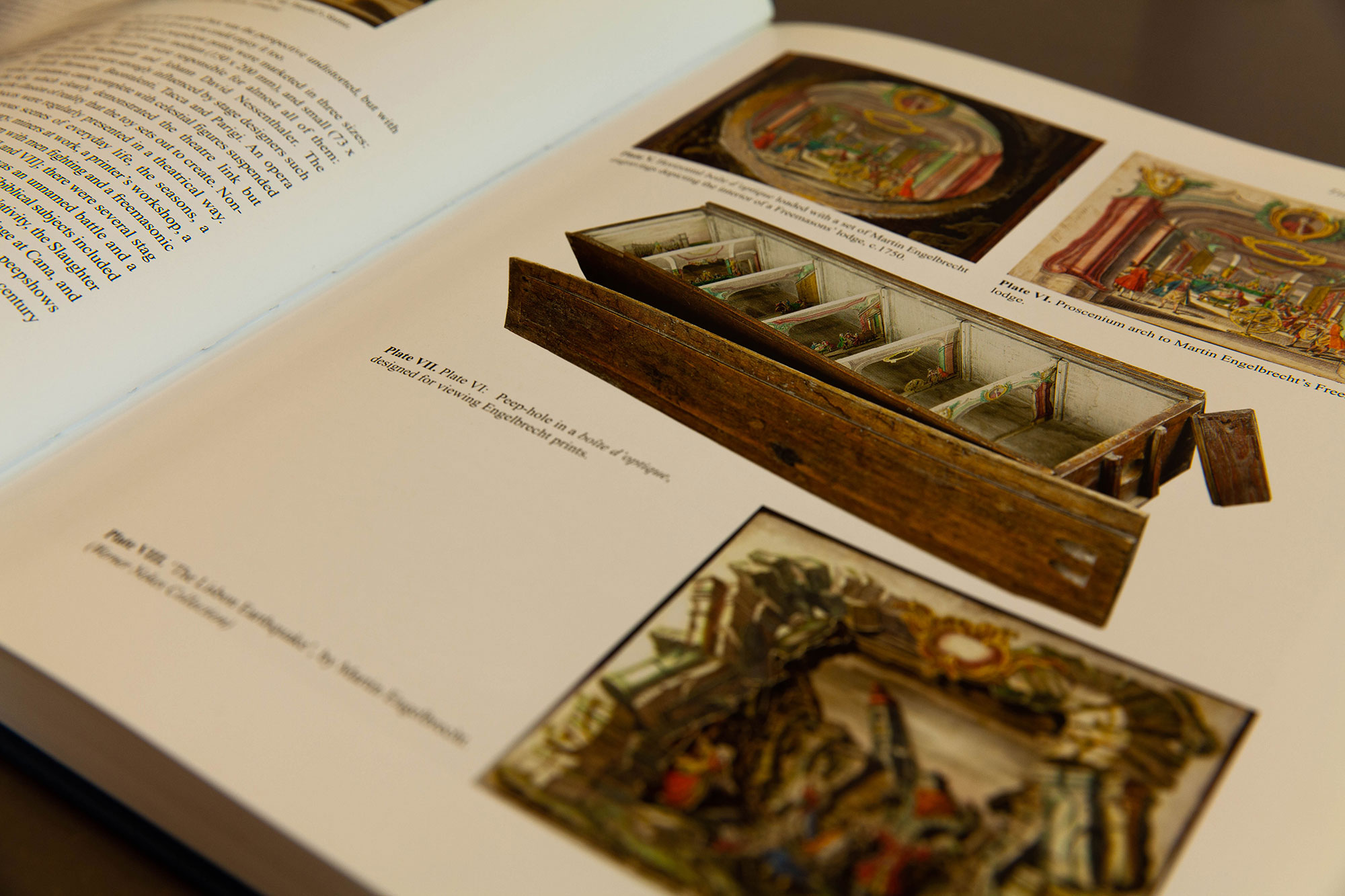

The book “Paper Peepshows” written by Ralph Hyde (1939-2015) provides another fine example of “peep media”. Starting point for the author’s research is the Jacqueline and Jonathan Gestetner Collection of paper peepshows housed at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London consisting of over 350 examples from around the world. Hyde sees the Baroque theatre, Sacri Monti – the sensational mountain scenery of Piedmont and Lombardy in northern Italy, as well as French and English pleasure gardens as obvious forerunners and inspirers of paper peepshows. The so-called teleoramas – Greek, tele (at a distance) and orama (a view) – make their appearance in the mid-18th century. It was the printmaker Martin Engelbrecht (1684-1756) who created artfully designed sets of prints that slotted into a boîtes d’optique. A wooden box with evenly spaced columns into which the engravings depicting scenes from exterior and interior spaces could be inserted. It allowed its user an unobstructed view of the stage scenery just like privileged occupants of a royal box at the theatre. Other viewing devices followed with an ever-expanding catalogue of subjects.

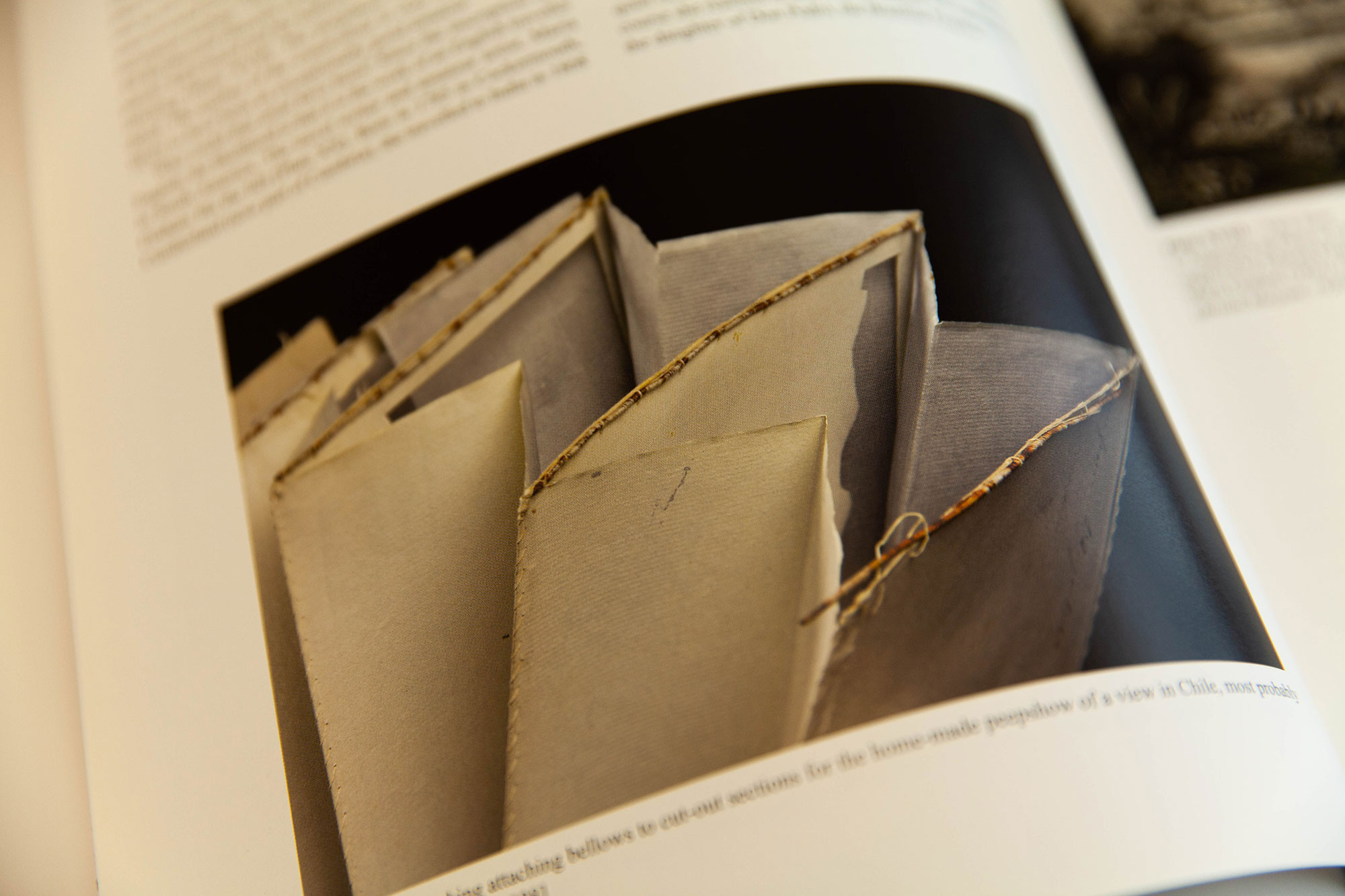

With an eager interest for peepshows, Heinrich Friedrich Müller (1779-1848) came up with a teleorama made entirely out of paper, making the wooden cabinet redundant. It consisted of a front board punctured by one or more peep holes, a sequence of cut-out panels and a back scene pasted onto a back board. Everything was held together by paper, sometimes by cloth. To protect the fragile construction it was often sold in a slip case. It was comparatively cheap and fitted neatly into a pocket. Around 1860, bookseller H. L. Hoogstraten issued twelve peepshow construction sheets designed for children to build and assemble their own paper peepshow. Paper peepshows are still produced today. Kara Walker’s (1969) “Freedom : A Fable”, 1997, or Anna Gaskell (1969) “Untitled”, 2001 are examples of contemporary peepshow creations.