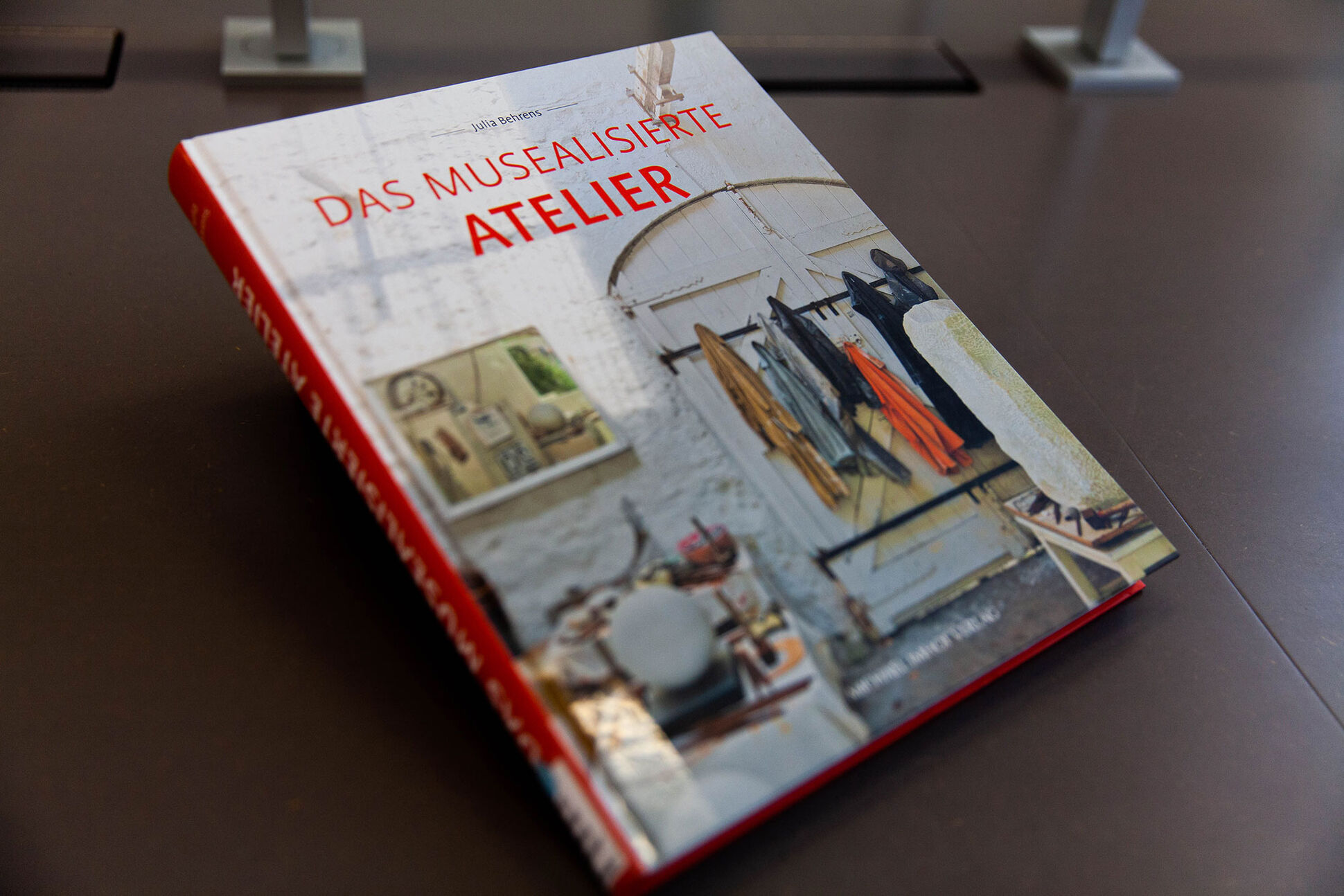

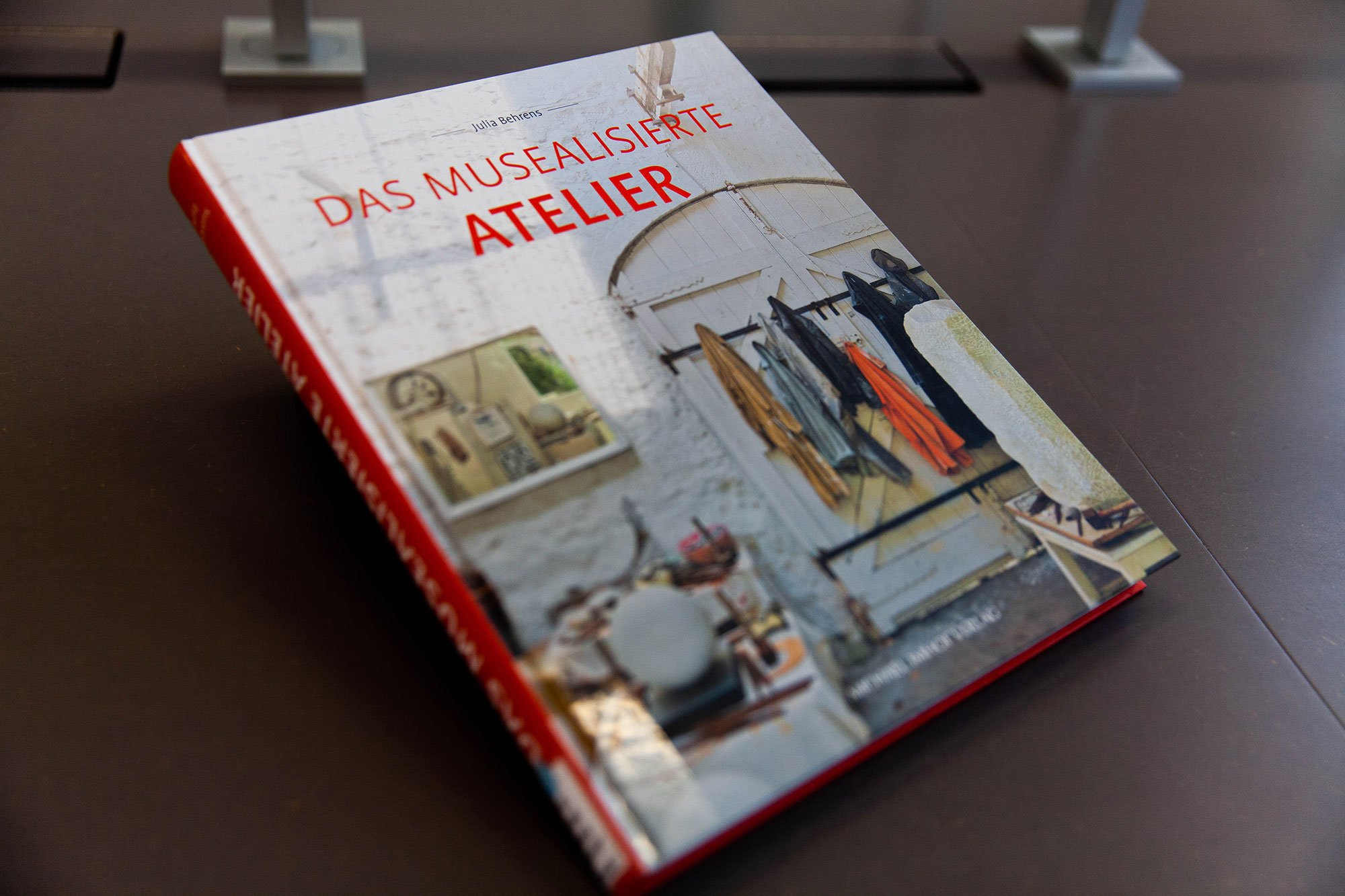

Julia Behrens (born 1966) follows these traces of artistic production with her dissertation, which go far beyond the fragments that are left behind. Her focus is on the conservation, translocation and reconstruction of artists’ studios. In this context, the musealisation of the studio space is not a novelty. Famous examples are the Rubenshuis in Antwerp, the Dürerhaus in Nuremberg or Constantin Brancusi's studio in Paris, to name but a few. In art history, the studio as an object of research was only systematically addressed in the second half of the 20th century. Parallel to this, interest in the "artist's house" grew. However, research, especially in this field, is rather heterogeneous, as individual studies examine the functional definitions and manifestations of the studio from different perspectives. An "artist's house" and "artist's studio" are often mixed up. In her observations, Behrens attempts to concentrate on the exceptional space of the "studio" and begins her research in the 19th century, when the mysterious space becomes increasingly interesting for a growing audience. The studio itself is also a subject first in painting, and from the late 19th century onwards in photography.

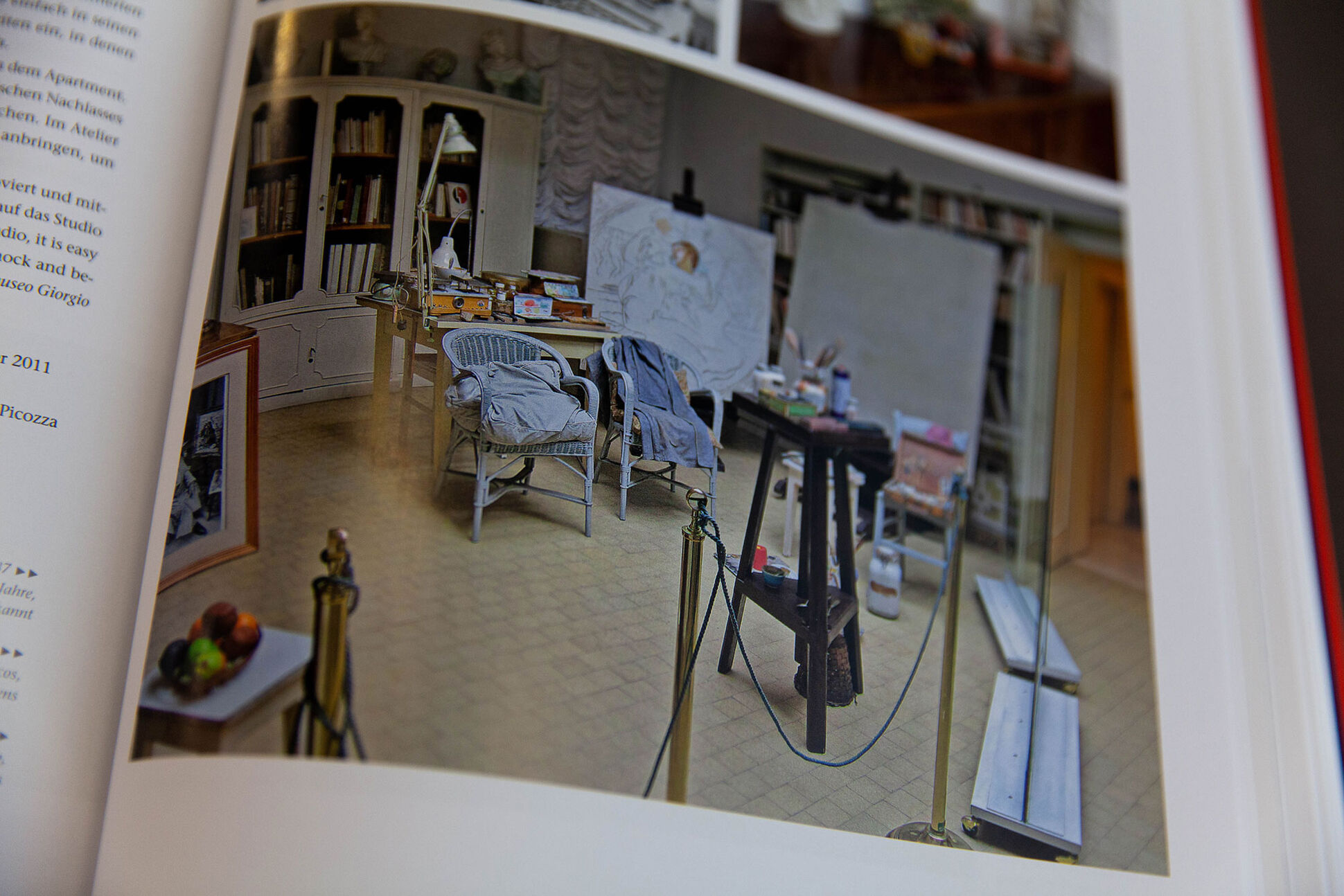

The art theorist Paul Schulze-Naumburg (1869-1949) describes the workspace of an artist in his book "The study and aims of painting" as follows: "do you know where art life is concentrated, what it is like for serious artists? In the drearily long, desolate streets, the studios are situated in rear buildings. Large bare rooms, whitewashed, into which only cold northern light falls; rarely is there another window or a glass extension. The furniture is modest. An upholstered seat or a flat divan, an antique cupboard, a few plain wooden stools, a large table for painting utensils. [...] The life of the modern painter is not as romantic as most people think."1 With the invention of new styles, the studio space also transforms. Furnishings, coloured walls such in the houses of the Bauhaus professors in Dessau, or Andy Warhol's factory lined with aluminium foil diverge from Schulze-Naumburg's description.

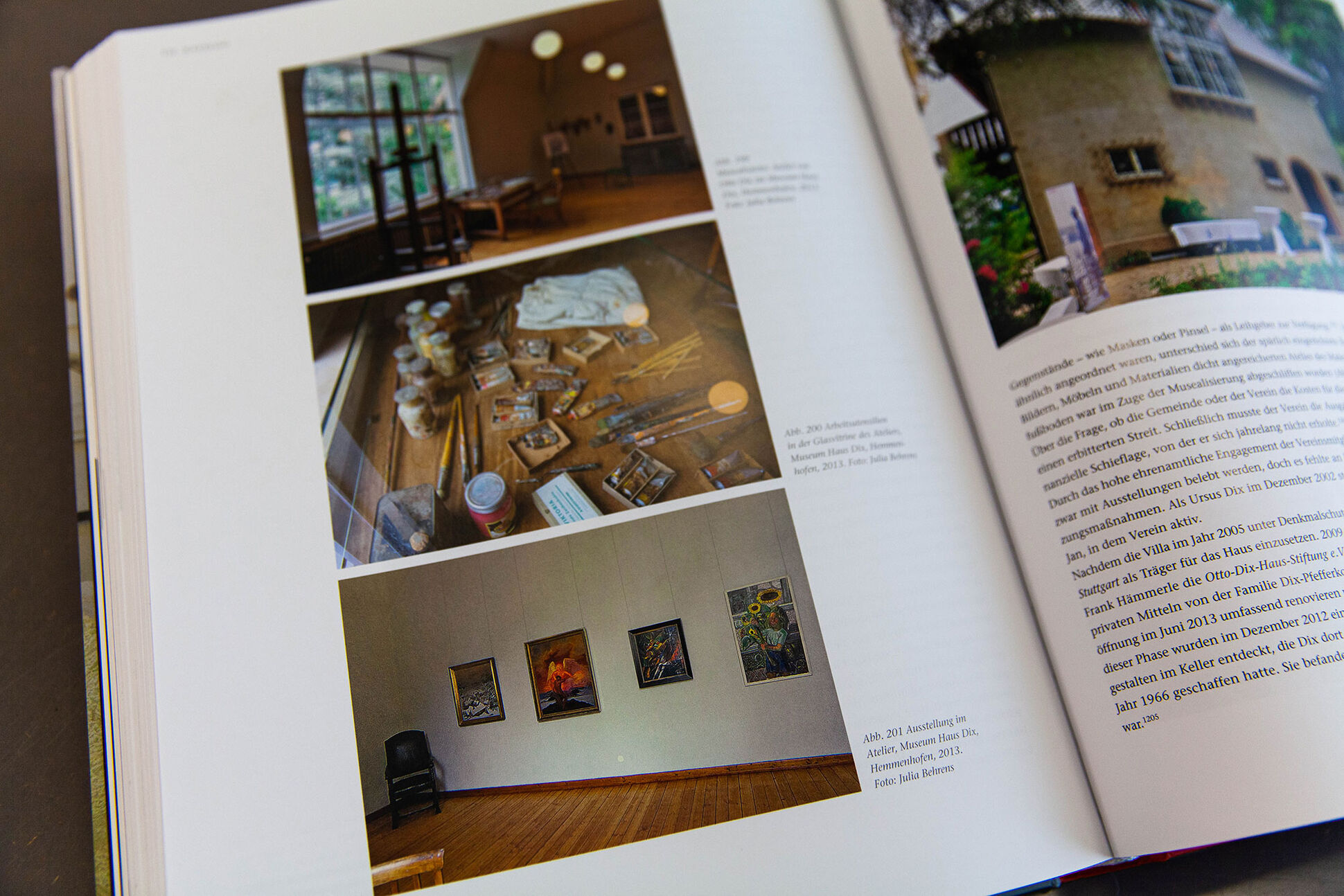

Yet the studio holds an insatiable fascination that leads to its musealisation. These spaces are not always preserved in their original locations. A very notable example of a translocation is the Brancusi Studio in Paris mentioned earlier. The studio becomes the object in a building constructed solely for the purpose of exhibiting it. Another example of a restoration and reconstruction of an existing studio is the barn, in which Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) worked. The building, which has be remodelled over the time, got restored to its original form and staged as a museum space after the establishment of a public foundation dedicated to its preservation. According to Behrens, preservation "in situ" seems the most common and natural way to preserve a studio. Behrens suspects that future solutions will be found in places "where the respective artists themselves are actively and creatively engaged in the preservation of the place of action that frames their own activity"2.

1 Schulze-Naumburg, Paul: Das Studium und die Ziele der Malerei, 3. Auflage, 1905, pp. 95-96; quotation in the present publication, p. 69

2 Behrens, Julia. Das Musealisierte Atelier, 2020, p. 170