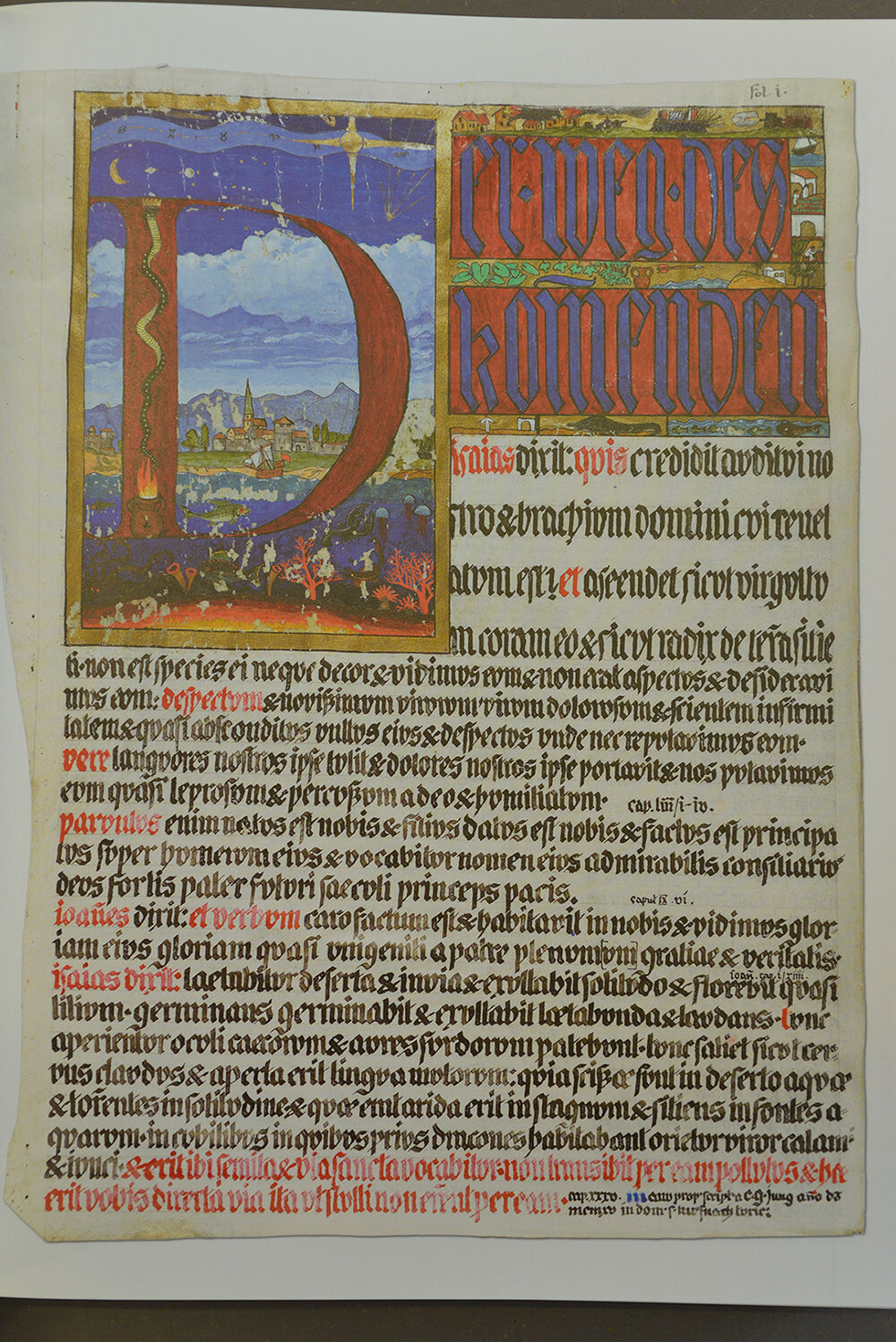

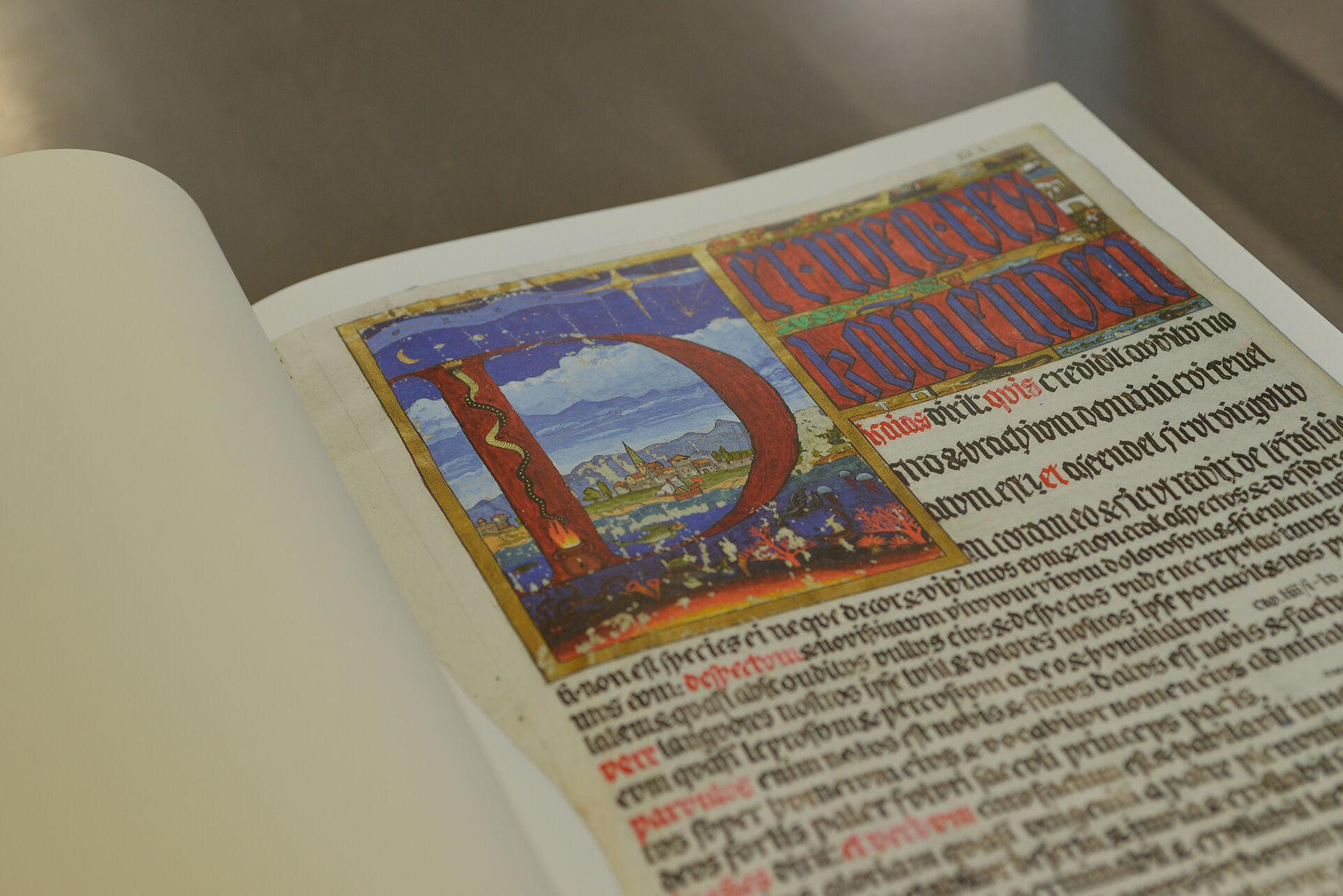

Even with regard to its content, it seems to follow the format of a book of hours, which was very common in the late Middle Ages in circles of the wealthy and literate nobility as a private devotional book. Moreover, certain parallels can be drawn between these types of books and Jung's manuscript, despite the fact that it is a psychological work in a literary form.

The existing calligraphic volume was preceded by Jung's notes, which he recorded as handwritten drafts in his preferred black notebooks from 1913 onwards. In turn, these were then transferred and revised in typescript, before he finally executed them artistically in the Red Book. This complex intricacy of each individual draft illustrates Jung's continued work on his own observations, which were deeply personal in nature and aspired to no scientific claim. In 1930 he ceased his work, leaving it unfinished. This perhaps explains why he did not pursue the publication of this book during his lifetime, although he did consider this step. When he died in 1961, he merely stipulated in his will that both the black notebooks and the Red Book remain in the family. In the early 1990s, the estate looked through Jung's unpublished material again, but it was not until the spring of 2000 that the decision was finally made to release the Red Book for publication. In 2009 it was officially published for the first time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, self-experiments were very common in medicine and psychology. The method of introspection was considered an important tool in psychological research. While Jung had previously projected his observations and findings onto a fictitious person, he realised in the course of his research that an analysis of his own unconscious processes was not inevitable: "As a form of thinking it was, I felt, altogether impure, a kind of incestuous intercourse, and intellectually completely immoral"[1]. His statement proves quite clearly that he had considerable resistance to overcome. His notes took the form of a dialogue between himself and his rational self instructing him. In Western philosophy, this dialogical form has been a common literary genre since Plato. Figures and ideas in Jung's explanations came directly from his preoccupation with mythological studies. Parallels can also be found in Nietzsche's "Thus Spoke Zarathustra" and Dante's "Divine Comedy", which influenced the structure and style of the "Liber Novus". This extended process of self-experimentation contrasted with Jung's everyday life; his job and family in this phase "always offered him a gratifying reality and a guarantee that I existed normally and really"[2].

Jung painted in tempera and wrote in ink in red folio volume. The paintings, initially pre-sketched in pencil, suggest a carefully composed design. His keen interest in the contemporary art of his time and his own highly developed technical skills in painting allowed him to closely intersect psychological and artistic experimentation. Jung was by no means the only one to realise his visions artistically. The Swiss doctor Alphonse Maeder (1882-1971) published his version under a pseudonym. Franz Beda Riklin (1878-1938) Swiss psychiatrist and painter, together with Hans Arp (1886-1966), Sophie Taeuber (1889-1943), Francis Picabia (1879-1953) and Augusto Giacometti (1877-1947), even exhibited some of his works at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1919. Many of Jung's insights gained from these processes of self-exploration are later included in his scientific psychological writings.

[1] Analytische Psychologie, S. 53

[2] Erinnerungen, Träume, Gedanken von C. G. Jung. Ein Buch von Aniela Jaffé und Carl Gustav Jung, 1961, S. 193