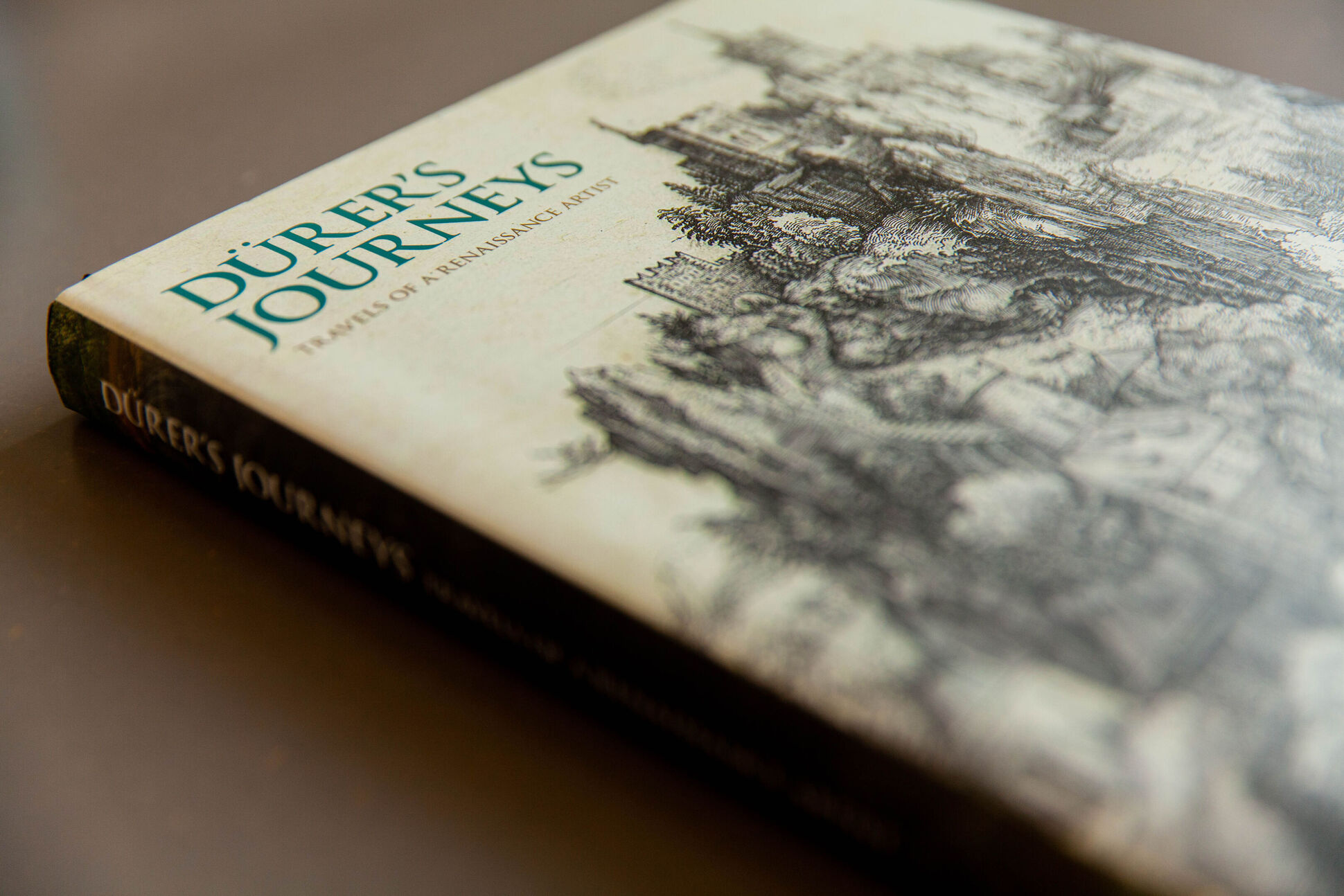

Paintings, works on paper, prints, surviving letters, diaries and sketchbooks by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) offer a very personal insight into his travels from Nuremberg to Colmar (1490), Basel (1492), Strasbourg (1493), Innsbruck, Trento, Venice (1494-1495 and 1505-1507) and along the Rhine to the Netherlands, Zeeland, Flanders and Brabant (1520-1521).

The essays in the exhibition catalogue provide a deeper insight and interpretation into the pictorial and written accounts. Not every journey can be conclusively reconstructed and has been documented in such detail as Dürer's journey to the Netherlands. The text by the curator Susan Foister (b. 1954) quickly reveals that even accounts written by contemporaries during Dürer's lifetime give varying accounts of his early travels. Only commissions and works convey a vague indication of his possible whereabouts. On the account of Dürer's ten letters written to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer (1470-1530) in Nuremberg can the second journey to Venice (1505-1507) be traced properly. The aim of the trip was to fulfil a commission issued by a German tradesman in Venice for the large-format altarpiece “The Feast of the Rosary”, 1506. However, the letters also provide evidence of the sale of his own prints, and thus the expansion of his distribution network for his own works, which had been established as early as 1497.

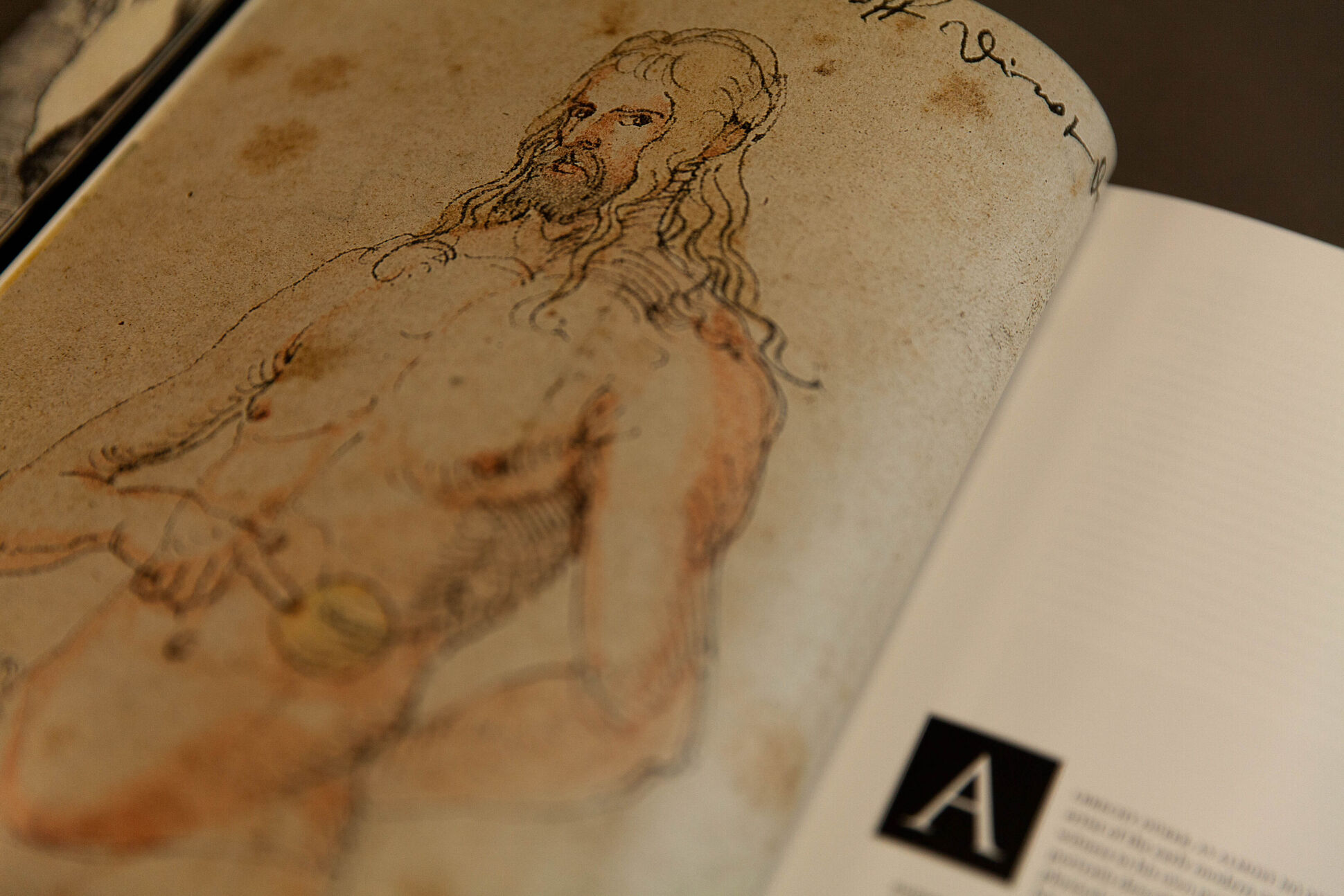

Dürer's so-called "Diary of the Dutch Journey" begins on 12th July 1520 with an entry about the start and destination of the journey; his companions - his wife Agnes and their maid Susanna; expenses spent in the village of Baiersdorf for the overnight accommodation and food; and general considerations about continuing the journey taking the water way in order to reach his destination more quickly. Both essays by the art historian Andreas Beyer (b. 1957) and that by the curator Christof Metzger (b. 1968) confirm that the diary was far more than just an autobiographical account of a journey. Unfortunately, the original has been lost, but two copies have survived. The diary documents travel stops and impressive sights, important meetings with artists, artisans, traders, members of royal households, patrons etc., details of meals taken, costs of accommodation, the artist’s physical condition and illnesses. It also provides information on works produced during the journey, as well as impulses and impressions that were remarkable enough to be recorded. An important part of the journey’s documentation is the silverpoint sketchbook, in which Dürer recorded impressions of his journey, thus adding a visual account to the written diary. The full extent of the sketchbook is not known. Nor have any drawings survived that illustrate the beginning of the journey. This leads the art historian Arnold Nesselrath (b. 1952) to assume in his essay in the exhibition catalogue that Dürer only began to fill the sketchbook with drawings at a travel stop in Aachen in October 1520. In any case, these sources offer surprising insights into an extraordinary artist's career.